International Review of Music

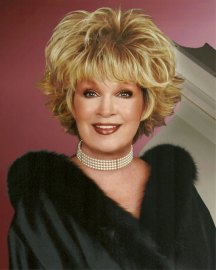

Live Music: Sue Raney and Alan Broadbent at Vitello’s

April 27, 2011By Don Heckman

On Friday night at Vitello’s, Sue Raney gave an unofficial seminar in the art of song. A seminar, that is, that illustrated by example, not by textbooks. And the key word was “art.” Because Raney’s remarkable vocal skills were completely at the service of her creatively illuminating interpretations of material from the Great American Songbook — and beyond.

The performance began impressively with a stunning solo rendering of Irving Berlin’s “How Deep Is the Ocean” by pianist Alan Broadbent, who would provide the sole accompaniment for Raney’s set. Long term musical companions, the near-symbiotic presence of Broadbent’s extraordinary support was immediately established as the launching pad for Raney’s soaring interpretations.

Her first song was the Burke/Van Heusen classic (most famously sung by Bing Crosby), “Aren’t You Glad You’re You.” Done with buoyant, whimsical charm, it immediately defined one of the many aspects of Raney’s story telling skills. A tender version of Dave Frishberg’s “Listen Here,” followed by a jaunty romp through Burnett & Norton’s pre-WW I “Melancholy Baby,” further revealed the breadth of her vocal art.

As did similarly insightful readings of Sherwin & Maschwitz’s “A Nightingale Sang in Berkley Square,” Rodgers & Hart’s “He Was Too Good To Me,” Warren & Gordon’s “You’ll Never Know” and David Raksin’s atmospheric theme from “The Bad and the Beautiful.”

The set hit its peak with stunning anthems to Spring — including Rodgers & Hammerstein’s “It Might As Well Be Spring” and Michel Legrand and the Bergmans’ “You Must Believe In Spring.” In the closing vamps, Raney light-heartedly tossed in quotes from other songs about Spring. And, more subtly, Broadbent slyly used the opening phrase from Clifford Brown’s “Joy Spring” as an introduction.

What Raney brought to all this memorable material was a stunning mix of craft and dramatic imagination, engagingly expressed via her warm-toned, far ranging voice — all of it combined in a perfectly balanced, utterly compatible musical blend.

I’m not sure how many singers were in the overflow crowd, but I know there were a few. And I’m willing to wager that they came away from Raney’s casual but mesmerizing seminar with some vital ideas about the enhancement of their own vocal art.

###

________________________

Heckman got the day of the week wrong. It was Monday. O'wise, he's spot on!

On Friday night at Vitello’s, Sue Raney gave an unofficial seminar in the art of song. A seminar, that is, that illustrated by example, not by textbooks. And the key word was “art.” Because Raney’s remarkable vocal skills were completely at the service of her creatively illuminating interpretations of material from the Great American Songbook — and beyond.

The performance began impressively with a stunning solo rendering of Irving Berlin’s “How Deep Is the Ocean” by pianist Alan Broadbent, who would provide the sole accompaniment for Raney’s set. Long term musical companions, the near-symbiotic presence of Broadbent’s extraordinary support was immediately established as the launching pad for Raney’s soaring interpretations.

Her first song was the Burke/Van Heusen classic (most famously sung by Bing Crosby), “Aren’t You Glad You’re You.” Done with buoyant, whimsical charm, it immediately defined one of the many aspects of Raney’s story telling skills. A tender version of Dave Frishberg’s “Listen Here,” followed by a jaunty romp through Burnett & Norton’s pre-WW I “Melancholy Baby,” further revealed the breadth of her vocal art.

As did similarly insightful readings of Sherwin & Maschwitz’s “A Nightingale Sang in Berkley Square,” Rodgers & Hart’s “He Was Too Good To Me,” Warren & Gordon’s “You’ll Never Know” and David Raksin’s atmospheric theme from “The Bad and the Beautiful.”

The set hit its peak with stunning anthems to Spring — including Rodgers & Hammerstein’s “It Might As Well Be Spring” and Michel Legrand and the Bergmans’ “You Must Believe In Spring.” In the closing vamps, Raney light-heartedly tossed in quotes from other songs about Spring. And, more subtly, Broadbent slyly used the opening phrase from Clifford Brown’s “Joy Spring” as an introduction.

What Raney brought to all this memorable material was a stunning mix of craft and dramatic imagination, engagingly expressed via her warm-toned, far ranging voice — all of it combined in a perfectly balanced, utterly compatible musical blend.

I’m not sure how many singers were in the overflow crowd, but I know there were a few. And I’m willing to wager that they came away from Raney’s casual but mesmerizing seminar with some vital ideas about the enhancement of their own vocal art.

###

________________________

Heckman got the day of the week wrong. It was Monday. O'wise, he's spot on!